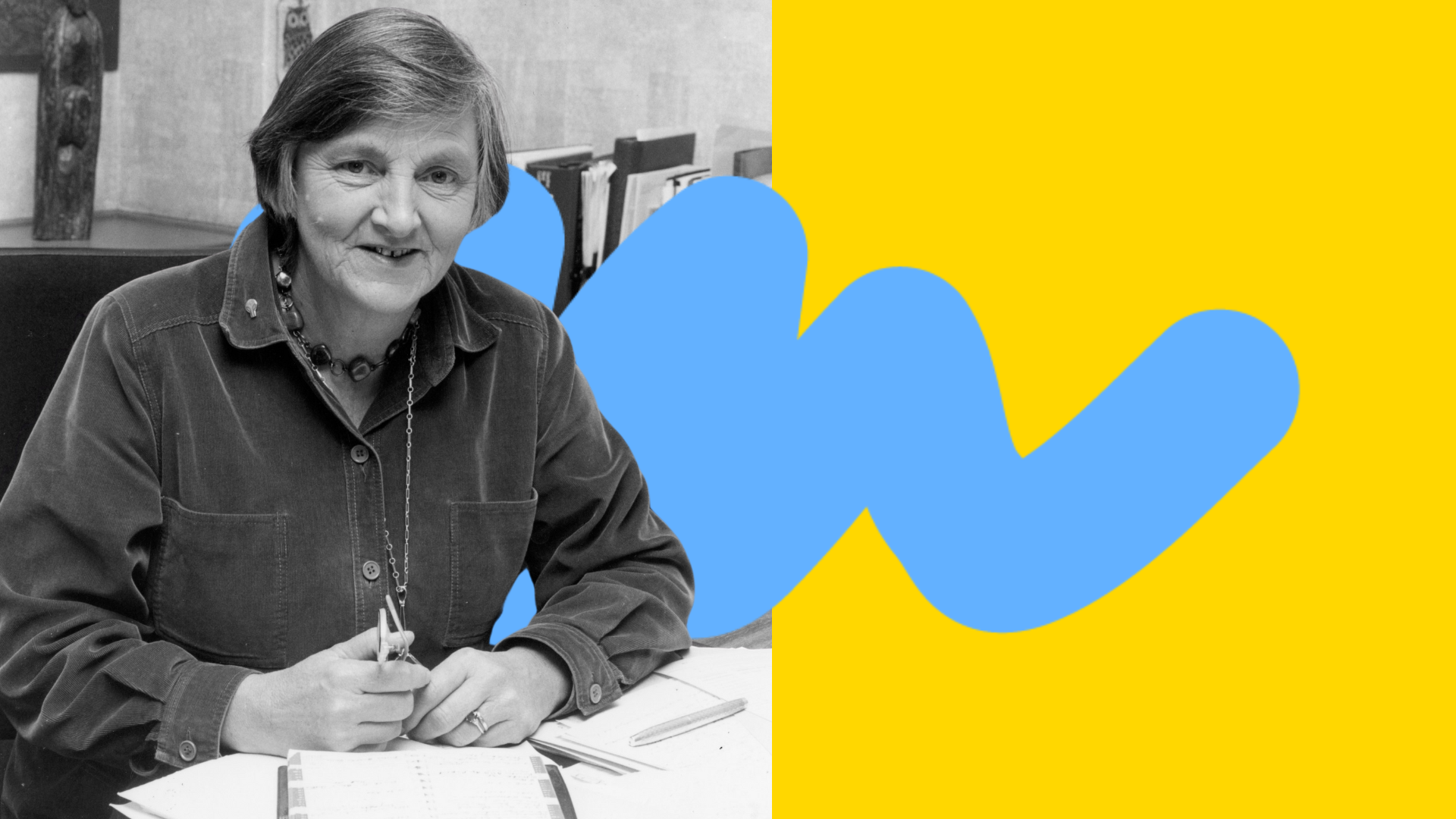

The Feminist Legacy of Fay Marles AO: A Eulogy by Mary Crooks AO

It was 1977 when Fay Marles became Victoria’s first Equal Opportunity Commissioner. She saw it as the chance of a lifetime: ‘I suspected that it was also going to change our lives in ways that I couldn’t yet foresee. I knew that failure in that role would kill any future career prospects, so I embarked on it with both excitement and trepidation’.

The trepidation was understandable for Fay was about to formally challenge, and try to change for the better, a very patriarchal world.

A marriage bar had been in place since 1890, stipulating that women in the public service who married must immediately retire. It was lifted only a decade before Fay started her Equal Opportunity role (but not before women like Fay and her contemporary, Joan Kirner AC, were denied the same continuity in career development as that accorded to men).

When Fay stepped into her role, there were no women in the Federal House of Representatives and only two in the Victorian Assembly. The Whitlam government had not long passed the Family Law Act allowing ‘no fault’ divorce – liberating vast numbers of unhappily married women. Under Whitlam too, refuges for women escaping family violence were being created across the country – not that they could go close to meeting the demand.

By 1977, only three states, South Australia, New South Wales, and Victoria had extended full jury rights to women, dispensing with long-held biases that women were irrational and not up to the task.

Just five years before, the Women’s Electoral Lobby had formed -advocating for equal pay, access to contraception, equal opportunity, abortion on demand and free childcare.

∗ ∗ ∗

The landmark Victorian Equal Opportunity Act of 1977, introduced under the Hamer government, specified there shall be a Commissioner for Equal Opportunity and that the Commissioner has the functions powers and duties conferred on him (my emphasis) by this Act.

Fay threw her hat in the ring. She was most taken aback when her application proved successful.

The law matters. It provides platforms for change. But let’s be clear — it is ultimately the caliber, personal qualities, motivation and the commitment of those who administer the law that is the most telling, and potentially, the most socially transformative.

Fay had seven staff. No one had worked in the area before. She had no budget. Unfazed, she educated herself to the task. She appreciated the support and wise counsel of trusted female friends. Otherwise, she had to rely pretty much on herself devising her own procedures, relying on principles of natural justice and as she put it, the techniques of social work.

Early on, she enlisted the help of Judge Judith Cohen who advised Fay ‘it doesn’t matter how you do it. You can conduct the meeting under a gum nut tree if you like. Whatever you do will be seen as the way it’s done in equal opportunity. Whatever you do, do it confidently and they will follow you’.

Fay did just that.

On the issue of restrictive and discriminatory dress regulations for women police officers, Fay sought to satisfy herself firsthand as to whether skirts and pantyhose disadvantaged them compared to men in trousers and long johns. After standing on point duty in the bitter cold, dressed as closely as she could to the policewomen, she was confident in calling out the discrimination.

My friend Toni told me last week of her own contact with Fay. She approached her office on behalf of the Young Christian Women’s Association softball group. Men’s cricket had commenced at Royal Park. It wasn’t long before their cricket playing area seemed to be creeping even closer to the women’s own play area – the respective outfielders were close to colliding with one another. Fay met Toni and her President – she recalled Fay as very welcoming, with an attentive ear. What’s more, Fay made it her business to come to Royal Park one Saturday afternoon to see the situation firsthand. She then got in touch with Melbourne City Council and the matter was resolved

It was early in the piece that the Deborah Lawrie (née Wardley) case catapulted Fay and her office into the limelight. It was an early acid test. It took 18 months from the lodgement of Deborah’s complaint before Deborah was able to become a trainee pilot with Ansett Airlines. In this time, there were three hearings before the Equal Opportunity Board, two before the Supreme Court and one before the High Court. Wouldn’t you love to have been a fly on the wall with Fay gently pressing Reginald Ansett on his opposition to women pilots — to finally establish that it was because they menstruated. (Just quietly, I also reckon Fay would have taken some satisfaction from the fact that a women’s boycott of Ansett Airlines resulted in something like a 20% drop in the airline’s revenue.)

Less public than this case, however, were issues such as male nurses seeking careers in obstetrics nursing. Fay recalled there were 10 metropolitan hospitals offering midwifery training and seven of these refused to accept men: she visited them all and after discussion of the issues most agreed to open their waiting lists for male nurses.

Conciliatory rather than combative. Considered rather than doctrinaire. Conflict, often more apparent, than real.

Fay understood and appreciated the power of culture in either facilitating or holding back social change.

She recalled going to Canberra at one stage to the area not unlike her own. ‘I was speaking to the head of the organisation who was a very pleasant man. He had a very well-cut suit. He had polished brogues. He was about 6 feet 2 tall, he had a beautiful haircut and a very nice voice. After we had been speaking for a short time, he said he would get his second in charge because we wanted to talk to him also. So he came in to be introduced. He was a tall man with a grey suit with polished brogues. By the time I had seen four of them, I knew that something was happening in that organisation in relation to selection.

She placed a premium on community awareness and education. In her view the growth of awareness and consciousness had the greater community effect rather than the strength of the legal safeguards and sanctions.

Remember she had no budget. Undeterred, she issued bulletin after bulletin about the common causes of discrimination. Cannily, she turned to organisations to circulate these bulletins to their membership — the Victorian Employers Federation, the Education Department, the Victorian Hospitals Association and so on. In plain English, the press liked them and they gave Fay free publicity on radio and TV.

Her very first bulletin related to several complaints she had received from women who were on female-only rosters to provide the morning and afternoon teas in their office. There were three grounds of complaint: it was belittling to make cups of tea for men at a more junior level than themselves; it interrupted their work and made them less efficient; and it made a major statement on the value of women’s employees in the organisation.

Fay noted that her 1979 Annual Report was the first to formally identify (in Victoria), sexual harassment as a workplace problem, known to exist but tacitly relegated. Her own personal experience of predatory male behaviour sharpened her appreciation of the vulnerability of women. For Fay, ‘sexual harassment was the one area where I felt I could be at risk of losing my objectivity because the complaints and their circumstances made me so angry’.

It took courage, she said, to make a complaint. She understood that ‘a victim’s reluctance to talk was part of the dynamic of sexual harassment’.

Fay was also attuned to what she saw was a deep problem of racial discrimination affecting Indigenous Australians: ‘Not only do Aboriginal children undergo the experience of being unrecognised by the Australian community as people of dignity and worth who have the right to recognition and investment of society’s social, emotional and material resources, but they are devalued by our conventional European outlook’.

In her view, it was essential to make her office as accessible as possible to the Aboriginal community. She appointed two new Indigenous conciliators.

∗ ∗ ∗

Hell hath no fury, like patriarchy scorned.

The backlash came thick and fast, until such time as Fay won the hard-earned and begrudging respect of many of the doubters.

In Fay’s eyes, ‘With the publicity surrounding my announcement, my own life changed dramatically. I became a public figure about whom everyone I met had an attitude. They were either for me or against me. It certainly sorted out friends and acquaintances. Some were delighted. Others thought I’d gone mad, and it proved to others what they had always suspected’.

Changemaking is tough and demanding. There was animosity, overt and covert hostility, awkward conversations: ‘Like the trade unions, employer organisations expressed great scepticism about the need for equal opportunity legislation and strong doubts about its workability. She recalled one public meeting where the head of a leading employment organisation said there was no indication that the new equal opportunity act was going to be administered sensibly, and it would be unlikely to survive for very long. Another referred to it as a paper tiger, the most likely effect being to give business more red tape’.

Fay later recalled feeling battered and bruised, battered by the bureaucracy and bruised by the employers.

Worse still, there were the death threats and the need for police protection. One time, Fay says she headed off an assault by a whisker.

∗ ∗ ∗

We stand on the shoulders of giants — not Cyclops, not Atlas, not Goliath for that matter. Fay was not a towering figure. She was around 5 feet five in the old language, but she was socially transformative. A trail blazer, paving the road for others to follow and inspiring many inspiring champions of equal opportunity such as Ro Allen and Kate Jenkins who are here to pay tribute to her.

She was firm and fair. Clear sighted. Purposeful. She elevated deep listening and finding solutions through conciliation. She was gritty and hardworking. There was no professional conceit. She was the ultimate quiet positive disruptor, her work leading to a widening and strengthening of provisions to deal with equal opportunity. Fay was canny, gutsy, humble and heroic.

∗ ∗ ∗

Martin Luther King once said ‘the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends towards justice’.

Fay’s life was geared towards justice. She never wavered in her support of equal opportunity, feminism and gender equality. Yes, progress toward freedom and equality was slow and attritional, but it was inevitable.

Her legacy is about justice. Fay would urge us on. After all, justice remains our hope, and our best chance.

Mary Crooks AO

Executive Director

Victorian Women’s Trust

29 November 2024

This eulogy was delivered at a memorial service held in memory of Fay Marles at Wilson’s Hall, University of Melbourne on Friday 29 November 2024. Other speakers included Amanda Smith, Jane Hansen AO, Jennifer Green, Elizabeth Marles, Prof Glyn Davis AC, Moira Rayner, Victoria Marles, and Richard Marles.