Lucia Osborne-Crowley on the importance of trauma-informed care

CW: Sexual assault

Lucia Osborne-Crowley is the author of I Choose Elena and My Body Keeps Your Secrets, two memoirs that deal with the aftermath of sexual trauma. Here, Lucia writes about the importance of trauma-informed care in clinical settings, and why it should be standard practice for the safety, empowerment and healing of all patients.

When I was fifteen years old, I was violently raped on a night out in Sydney by a stranger with a knife. The assault left me deeply traumatised, but I didn’t realise it—because I knew nothing about the physiological symptoms of trauma, and so I had no way of recognising them for what they were. Instead, I committed myself to never thinking or speaking about the assault, convinced that my cognitive willpower could erase what had happened.

Here’s what happened to my body while I was trying to outrun my rape—first, I developed nightmares. Flashbacks that would terrorise me throughout the night. Second—and relatedly, I developed insomnia. Then, I started getting tremors in my hands and starting becoming clumsy, losing my balance. Finally, six months after the assault, I was struck down by a piercing pain in my abdominal, and associated vomiting and pelvic bleeding. I never connected any of this with what had happened.

I now know, as a 29-year-old, that all of these things are textbook early symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder. If any of the doctors I consulted during that time had known this, I think my life might be very different now.

I went to my GP as soon as I started having nightmares, and when I stopped sleeping I was seeing my GP regularly. I then started seeing specialists as soon as I was admitted to hospital with piercing abdominal pain. But no-one connected the dots.

Until one night, about a year later, I lay in a hospital bed after a diagnostic surgery. The emergency doctors suspected Crohn’s disease—which came up negative that night, but which I would eventually be diagnosed with five years later. One of the doctor’s came to see me and said, very frankly, “have you ever been sexually assaulted?”

I lied to him that night, because I was so committed to keeping my secret. But his question stayed with me for ten years. It planted a seed somewhere deep inside my brain. It was the beginning of a trail that I would return to years later and follow to its conclusion: that the physical trauma of my rape was connected to all of my symptoms.

Reflecting on that night now, two things strike me: the first is how badly I wish I had told him the truth, how it might have changed things. But the second is that given that that one question planted something in my mind, imagine how my life would have turned out if not one, but every doctor I interacted with was aware of the connection between trauma and illness.

I didn’t disclose my rape until I was twenty-five. In the intervening decade, I had become very, very sick. And not a single doctor asked me if anything traumatic had ever happened to me.

The reason I finally told my doctors about my assault was that by twenty-five, my illness had become so severe that I could no longer work, socialise, or function in any meaningful way. I couldn’t stay out of hospital. The abdominal pain was getting worse each year and new symptoms were developing all the time. No treatments worked, and the longer I spent lying in a hospital bed, the more I started thinking about that other night in a hospital bed, years earlier, the one where a kindly doctor had asked me if I had ever been assaulted. Finally, I thought to myself: I’ll do anything to get better. Even this. Even share the secret I promised myself I would take to my grave.

I wish it hadn’t had to get that bad before I finally sought help for my trauma and sought out doctors who understood the connection between trauma, chronic illness and chronic pain. I wish that path had been available to me ten years earlier.

My story makes me furious, looking back on it now—and it makes me determined to advocate for proper trauma training for doctors of all specialties, and particularly for emergency room doctors. If more doctors are trauma-trained, these kinds of situations can be avoided.

“The physical body can no longer be considered separate to the mind,” Joan Haliburn, a lecturer in psychological medicine at the University of Sydney, told me in an interview last year. “Trauma-informed care must be introduced – a system that addresses all patients with trauma in mind.”

Trauma-informed healthcare means making sure that doctors know how to spot the signs of trauma when a person presents to a GP or to a hospital. It means being able to look past the symptoms that the patient is reporting and spot a potential traumatic event as their underlying case—as the thing that connects up all the dots.

“Trauma has been linked to many medical conditions, including, but not limited to autoimmune diseases like Crohn’s, Rheumatoid Arthritis and Lupus, heart disease, diabetes and hypertension,” Dr. Linda Henderson-Smith Director for Children and Trauma-Informed Services at the National Council for Behavioural Health, said.

So what does trauma-informed medical care look like? As in my case, it has to start with asking the right questions.

“Patients often do not volunteer such information about prior experiences, because of guilt or shame,” explains Dr L. Elizabeth Lincoln, a primary care physician at Massachusetts General Hospital, in an article for an article published through Harvard Medical School.

A simple question such as, “Is there anything in your history that makes seeing a practitioner or having a physical examination difficult?” could make all the difference, she explains.

“Trauma-informed care is defined as practices that promote a culture of safety, empowerment, and healing,” Dr Lincoln says.

I’d like to see this approach being taught in every medical school across Australia. That way doctors can see the signs, and ask the right questions, to help patients access trauma treatment without having to wait ten years and countless hospital admissions before getting the help they need.

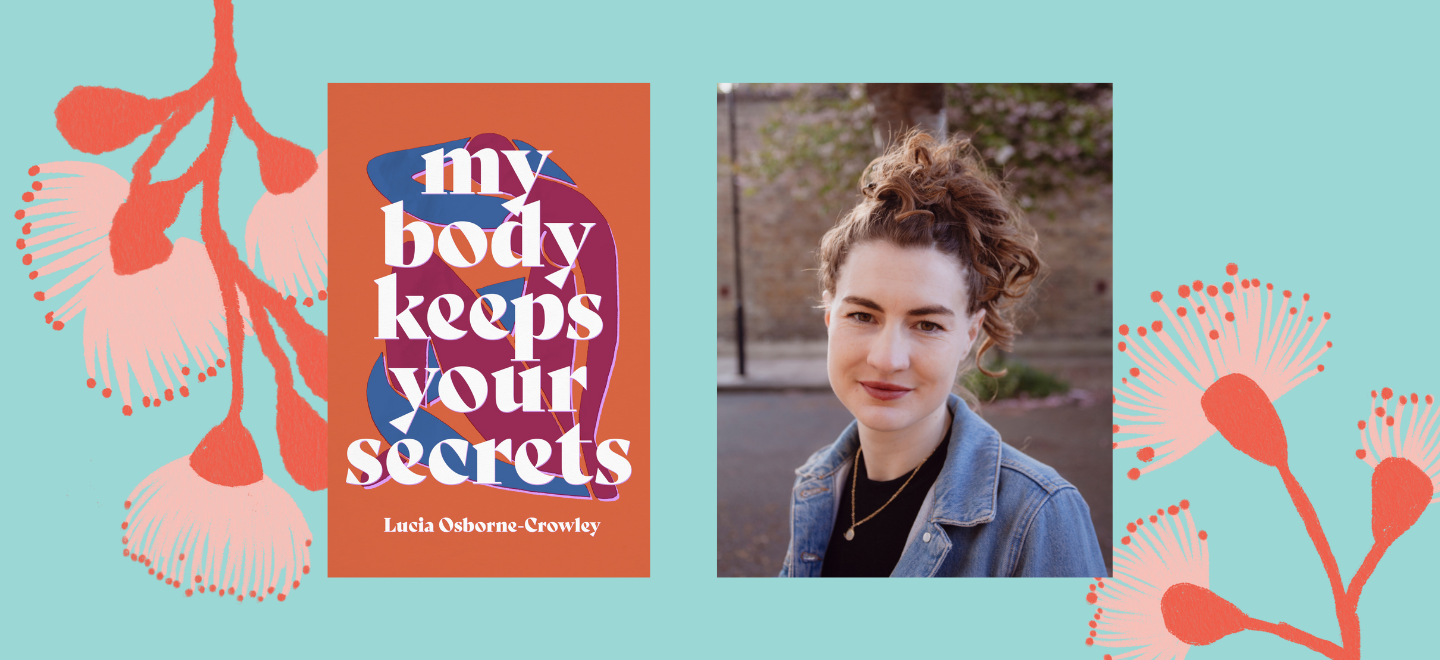

Lucia Osborne-Crowley is a writer and journalist. Her news reporting and literary work has appeared in Granta, GQ, The Sunday Times, HuffPost UK, The Guardian, ABC News, Meanjin, The Lifted Brow and others. She currently works as a staff reporter for Law360.

Her first book, I Choose Elena, was published in 2019 and her second book, My Body Keeps Your Secrets, was published in September 2021.

Read Next

A message to journalists reporting on violence

Blog"I’ve been writing about the erasure of men’s violence against women in the media for over a decade now. I’ve written articles, started the FixedIt social media campaign, studied it university and written a book about it. So, I guess by now you could almost call it an obsession."

Read more

Agency & Resistance: Centring the Voices of Survivors in Violence Prevention

BlogCatch up on 'Agency & Resistance', a violence prevention webinar with Nicole Lee, Fiona Hamilton and Jess Hill.

Read more

Georgina Savage on making The Trap

BlogGeorgina Savage is a documentary filmmaker, audio producer and podcaster. She is the co-creator and editor of Silent Waves (2018), co-creator, host and editor of...

Read more